Anyone who has read a gardening book or picked up a plant at their local nursery is likely familiar with hardiness zones. The USDA’s Plant Hardiness Zones map, which was updated recently, helps you to pick the plants for your yard.

In this article, we’ll delve into the importance of hardiness zones, the nuances of the updated map, and how the zones help with your yard. As a result of the map update, you may discover your local gardening zone now falls within a warmer category.

This latest update to the USDA Plant Hardiness Zone opens the door to new planting possibilities and invites you to experiment with and embrace plants that are now viable planting options.

- What are USDA hardiness zones?

- Why are plant hardiness zones important?

- Notable changes to the 2023 hardiness zones map

- What do the hardiness zone changes mean for gardeners and growers?

- Determining your hardiness zone

- Using hardiness zones to choose plants for your yard

- FAQ about the USDA hardiness zones

What are USDA hardiness zones?

The USDA Hardiness Zones Map’s designations may look like seemingly simple number and letter combinations, but they hold great importance when picking plants for your yard. Created by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1960, the hardiness zones map designates what plants can survive as perennials in climates across the U.S.

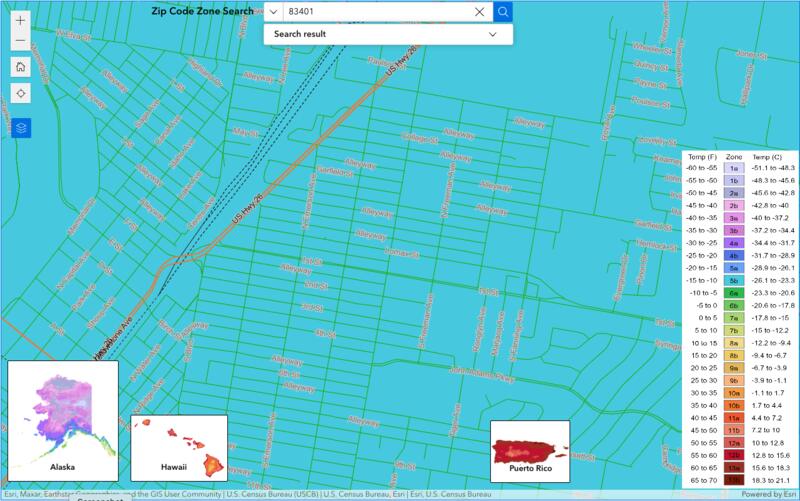

On the map, the United States is divided into 13 plant hardiness zones — designated as “1” through “13.” Each zone represents a 10-degree Fahrenheit range of average annual minimum winter temperatures. The zones are then broken down into two subzones of 5-degree increments noted as “a” and “b.”

The temperature scale on the planting zone map spans from -60 degrees Fahrenheit in Alaska (zone 1, region “A”) to 70 degrees Fahrenheit in Hawaii and Puerto Rico (zone 13, region “B”).

The updated 2023 USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map (PHZM) reflects the climate shift gardeners, landscapers, and farmers are experiencing worldwide, demonstrating changing times and the need for adaptability.

Changing season temperatures are reshaping landscapes across the country — influencing the varieties of plants that thrive in certain areas and how we tend to them.

Why are plant hardiness zones important?

All plants are hardy to a certain degree, meaning they can survive different conditions, such as changes in temperature or precipitation amounts. However, plant hardiness, especially cold hardiness, varies wildly.

When growing plants outdoors, it’s essential to know how hardy a plant is to determine whether it will thrive.

The USDA created the hardiness zones map to help gardeners choose plants for their landscape. Hardiness zones directly indicate a plant’s ability to survive outside through a winter season. For example, an annual or perennial in a region may thrive, but struggle to survive in or die in another region.

What’s the difference between annuals and perennials?

- Annuals grow for only one season, dying off as temperatures drop in the winter. They need to be replanted yearly.

- Perennials survive through the winter — although they may die back to the ground — and regrow each spring.

A plant will grow as a perennial if it is rated for a specific hardiness zone number. This means it can (typically) survive the minimum annual winter temperature. If it isn’t rated for a zone, the cold temperatures will kill it, making it an annual plant in that area.

Knowing your zone helps you choose hardy plants that can survive through the winter and come back as perennials.

Notable changes to the 2023 hardiness zones map

The 2023 map represents a collaboration of the USDA, the Agricultural Research Service (ARS) and Oregon State University’s (OSU) PRISM Climate Group. It draws on a much larger data set, using temperatures from 13,412 weather stations across the country — a significant increase from the 7,983 when developing the 2012 hardiness zones map.

The updated map is considerably more accurate and contains more details than prior versions by including significantly more data.

One significant advantage of this more extensive data set is the improved resolution of the rendering for Alaska. Before, the resolution was at approximately 6.25 square miles of detail; now, the map’s rendering is at a more impressive one-quarter square mile area of detail.

But Alaska’s improved rendering isn’t the most prominent change on the updated map.

What has people talking is this version shifts about half of the United States from its previous hardiness zone to the next warmer half-zone. The bump to the next warmer subzone means almost 50% of the country warmed between zero and 5 degrees Fahrenheit.

The other half of the country stayed in its previous subzone. That doesn’t mean winter temperatures there haven’t changed. It’s just that these areas, primarily in the South, didn’t have a big enough increase in temperature to bump them to a warmer zone.

According to Chris Daly, a researcher at Oregon State University’s PRISM Climate Group, the lowest likely winter temperature overall across the lower 48 states is 2.5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer (1.4 degrees Celsius warmer) than when the last map was published in 2012.

What areas are affected the most?

When you toggle back and forth between the 2012 and 2023 growing zones maps, a band of states across the Intermountain West, the Great Plains, the Midwest, and up through the Mid-Atlantic show a noticeable change in their zone coloration.

The colder zones designated by deep blues and purples are shifting north, replaced by softer shades of the same color and even a wide swath of green. The color changes in states such as Idaho, Wyoming, South Dakota, Indiana, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Maine quickly caught my eye.

Daly also told The New York Times that Arkansas, Kentucky, Missouri, and Tennessee had the most prominent changes and are as much as 5 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than the previous map.

What do the hardiness zone changes mean for gardeners and growers?

A change in a 5-degree subzone may not seem like much, but this small bump in winter low temperatures is being noticed.

Gardeners and farmers are seeing less winter damage to their plants, allowing them to reassess the plants they’re accustomed to growing. Landscapes are turning green earlier in the spring, giving way to lengthier growing seasons.

Over the last five years, I’ve seen sage and thyme successfully overwinter in my vegetable garden to grow as perennial plants. In the early 2010s, when I first started growing herbs, winters in Southeast Idaho decimated them, and they had to be planted as annuals.

But this slight shift in temperatures also brings challenges that must be addressed.

Wider opportunity possible species

A noticeable change is in areas such as Omaha, Lansing, and Boston, which have switched from 5b to 6a, going from blue to green on the map. While it seems insignificant, this change opened the door considerably to what gardeners can now successfully grow as perennials.

Plants typically known for growing in the warmer South may now survive winter temperatures in Nebraska, Michigan, and Massachusetts with little to no frost damage. Homeowners may tuck magnolias and camellias in amongst their northern red oaks without going to great lengths to protect them from December to March or April.

Longer growing seasons for more harvests

In regions experiencing this zonal warming, gardeners and growers may have the chance to expand their harvests.

Consider, for example, northern gardeners, who have been historically limited to two harvests per growing season. With warmer conditions, they might now experience longer seasons conducive to a third harvest, similar to their counterparts in warmer climates.

Increased pressure from weeds and invasive species

On the downside, though, warmer zones may encourage the spread of lawn pests and invasive species previously kept in check by cold temperatures.

Insects, diseases, weeds, and non-native pests that used to die off during cold winters may now survive and wreak havoc come spring. With the potential to push out native plants and pollinators, these pests may disrupt local ecosystems and compromise traditional farming and gardening practices.

One noteworthy example is the off-putting, aggressive Callery pear. These fast-growing, repulsively odoriferous trees are detrimental to native grasses and other species in areas.

For many years, though, Callery pears could not produce viable seeds, which kept them from reproducing and contained their spread. With this trend of warming winters, these ornamental pears may successfully reproduce and threaten landscapes.

Fewer chill hours for fruits

The warmer zones may also mean reevaluating fruit cultivars grown in specific areas for decades. Take blueberries as a prime example.

The beloved berry bushes have particular “chill hour” requirements — necessary periods of cold temperatures required for the bushes to set fruit. Growers that previously had the perfect winter chill conditions for varieties like the Northern Highbush now see fewer chill hours and disappointing yields.

To adapt, growers and gardeners must replant their berries and grow new-to-them varieties that thrive on fewer chill hours.

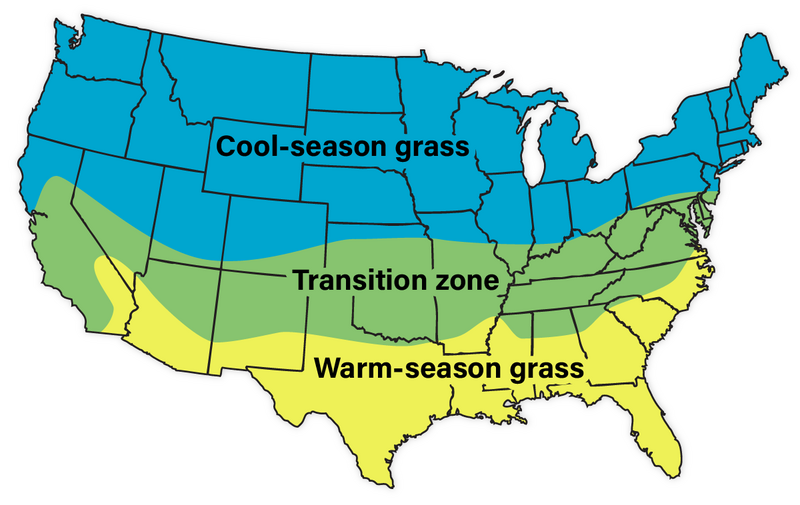

Will this affect the transition zone boundaries for growing turfgrass species?

The transition zone is an area across the central United States where the warm area from the South swirls with colder, northern temperatures. The “not too hot” and yet “not too cold” climate makes it hard for homeowners to choose between warm-season and cool-season lawn grasses.

As it stands, the boundaries of the transition zone appear fluid depending on the map you’re looking at. In some instances, Iowa is firmly north of the transition zone boundary; in others, the southern part of the state is included.

Little has been mentioned about whether the changes on the updated hardiness zones map will affect the turfgrass cold season, warm season, and transition zone boundaries.

However, if we’re seeing a gradual increase in minimum winter temperatures in the northern part of the country, it wouldn’t be surprising to see the transition zone moving to higher latitudes in North America. As more locations can grow plants historically reserved for the South, those same locations may soon have the ability to grow southern grasses, too.

Determining your hardiness zone

Let’s move on and talk about using the hardiness zones in your yard to pick plants.

Finding your garden zone is pretty straightforward with a broadband internet connection. The USDA Plant Hardiness Zones Map is an easy-to-navigate interactive map based on GIS (Geographic Information System). To find your plant hardiness zone, just click on your state or type your ZIP code into the search box.

Once you key in your ZIP code, you’ll see your hardiness zone and the average annual coldest temperature for your location. For example, if you type in the ZIP code for Idaho Falls (83401), the map shows you are in Zone 5b, with minimum temps between -15 to -10 degrees Fahrenheit.

You can then “click to zoom” and the hardiness map will zoom in on the location entered. Then, pan and pinch using your touchpad or fingers to find your home’s location and double-check the map’s color with the legend on the right side of the page.

Pro Tip: The ZIP code feature gives the most common zone; it’s always possible you live in a spot slightly warmer or cooler than the surrounding areas because of elevation changes, higher wind speeds, etc.

Using hardiness zones to choose plants for your yard

Now that you know your USDA zone, you can use it to select plants suitable for your area’s winter climate that should survive to grow as perennials.

Finding plants is typically much easier when shopping at your favorite local nursery — especially a smaller, family-owned business. Usually, these stores only stock and sell plants rated for your planting zone. They want your gardening adventures to be successful, so they won’t try to sell you something that won’t survive your cold winter temperatures.

Shopping from a catalog or your favorite online retailer gets a little more complicated. This is where you must do more work and match plants to your hardiness zone.

The catalog or online plant description should list basic growing conditions needed for the specific plant, including “hardiness zone” or “zone.” You’ll often see a range of zones, such as 8 to 10 or 5 to 9. The plant should fare well in your yard if your zone is within that range.

For example, if you check the label of Jackmanii clematis vine, you’ll see it’s rated for hardiness zones 4 through 9. Since Idaho Falls, Idaho, is designated 5b, this beautiful climbing flowering vine can grow and thrive in this area of the Snake River Plain. Even with frigid below-zero low temperatures and moderate amounts of snow.

On the other hand, one of my favorite flowers, the gerbera daisy, is listed for hardiness zones 8 through 11. There’s no way that stunning beauty will survive the winters here. It’s more suited for the warmest growing zones of the country, like those in Florida or Georgia.

If I want to grow them in my yard, I’ll have to resign myself to replanting new ones each spring, knowing they’ll only be annuals.

Looking beyond your hardiness zone

Even if a particular plant is rated for your hardiness zone, it isn’t guaranteed to thrive in your yard.

A hardiness zone rating tells you the average annual minimum winter temperature a plant can typically withstand. It doesn’t tell you:

- How much sunlight the plant needs

- The maximum temperature it can tolerate in summer

- Precipitation requirements

- What type of soil it prefers

You must also consider the other characteristics listed on the plant tag or in the product description. It’s critical to match a plant’s care requirements to the growing conditions in your yard so it gets the right amount of sun and the soil type it likes.

Just because a plant can survive the winter in your climate zone doesn’t mean it will thrive in your landscape.

FAQ about the USDA hardiness zones

What is plant hardiness?

A plant’s hardiness describes its ability to withstand adverse growing conditions, usually pertaining to climate characteristics. Usually, a plant’s hardiness relates to its ability to withstand cold temperatures, heat, drought, flooding, and wind.

Can I plant things that aren’t recommended for my zone?

While it isn’t recommended for beginner gardeners, you can still plant things not recommended for your region.

First and foremost, you can always plant them as an annual and buy new ones every spring. If you want to (try to) grow them as perennials, it will require more time and effort; they’ll need extra protection to survive the winter.

Keeping out-of-zone perennials alive through the winter may be possible by creating a microclimate. The best way to do that is to grow these plants in raised garden beds and ensure plants are insulated through the winter by growing them in cold frames or protecting them under thick layers of mulch.

Keep in mind, too, that there are some limits to this. You shouldn’t try planting something designated for Zone 9 if you live in Zone 5. Growing a flower, for example, in a container and bringing it indoors when it’s cold would be easier.

Who uses the USDA plant hardiness zones map?

The most frequent users of the Plant Hardiness Zones Map are the approximately 80 million American gardeners and growers across the country. It is also referred to by the USDA Risk Management Agency to set specific crop insurance standards, and many scientists looking at the spread of weeds and insect pests incorporate hardiness zones as a data layer in their research models.

Need help with choosing plants for your yard?

As with all things, change can be hard to adjust to. In the case of this updated hardiness zones map, the change may be favorable and let you plant something new and exciting you’ve never tried before.

If you need a hand navigating plant hardiness ratings and zones or help to choose plantings for your newly designed warmer zone, reach out to Lawn Love. We’ll put you in touch with local, high-quality landscape professionals who can select the right plans for your hardiness zone to create the yard and garden of your dreams.

Main Photo Credit: U.S. Department of Agriculture