The difference between plants and a garden is design. Native plants are a hot topic for homeowners, but how do you create an Instagram-worthy design? We’ve got tips and tricks on how to design a native plant garden that your followers will “ooh” and “aah” over.

Design fundamentals of a native plant garden

Design principles apply across the artistic realm. Use these principles whether you compose an opera, choreograph a dance number, or plant a garden. Let’s dig in.

Balance

Balance is often achieved by creating symmetric or asymmetric designs across an imaginary line. A symmetrically balanced design creates a mirror image across the midpoint.

- Example: Formal English gardens often use symmetry to create balance.

Focalization

Focalization guides visual direction or traffic toward a feature in the landscape. It may be simpler to say, include a focal point as you plan your garden design.

- Example: A statue, ornamental bed, large tree or shrub, or point on the horizon that you want to direct people to.

Proportion

Proportion is the relationship between elements.

- Example: The relationship between tree height and building height, or the relationship between different plant heights in the garden.

Repetition

Repetition refers to using similar elements multiple times within the landscape. This creates a sense of cohesion.

- Example: Using a single tree species to demarcate a property line or border.

Rhythm

Rhythm in a design helps create movement. Repetition is key. Repeated use of line, color, form, or other elements create movement through an entire landscape.

- Example: A winding path with curved lines helps to direct visitors through the landscape. Similarly, a pathway lined with trees (repetition) directs the visitor toward, perhaps, a fountain at the end of the walk.

Simplicity

Simplicity is the idea that a designer should keep only the elements that contribute to the design’s unity and coherence. It does not imply a lack of complexity or interest. If a landscape lacks organization or unity, it lacks simplicity.

- Example: Focus on a single idea or garden theme and stick to it (for example, a Japanese, cottage, desert, or kitchen garden). Don’t mix and match. This usually leads to a chaotic appearance.

Transition

Transition refers to a “gradual change” in shape, size, or color.

- Example: The flow in height from groundcover, to small perennial, to shrub, to tree.

Unity

Unity is the “main idea” of your landscape. Practically, this is closely related to the theme, such as cottage garden, Asian garden, or formal garden. It also considers how well the garden fits with the space or climate. Unity is the sum of the successful use of all other elements.

- Example: Does a cottage garden look like a cottage garden? Cottage gardens look informal and naturalistic, using local materials, such as trees and stone, to create garden beds and fence lines. They are often associated with the look of the rural English countryside. Decide on a theme and stick to it, and you’ll likely achieve unity in your garden design.

To find out more about the principles of creating a native garden, check out:

- Circular 536, “Basic Principles of Landscape Design” from the University of Florida

- “Principles of Landscape Design,” a slideshow presentation from Clemson University

- “Principles of Landscape Design” from Michigan State University

How to plan for a native garden

Before you head to the check-out line with a basket full of plants you’d like to install, do a little pre-planning work.

Size up the sun

Location, location, location. Once you’ve marked the location for your new native plant garden, spend one day to track the sun in this space. Determine whether you have full sun (six or more hours of direct sun), partial sun (sometimes called partial shade: two to six hours of direct sunlight), or full shade (less than two hours of direct sunlight).

Know the soil

Sun and soil comprise the building blocks for any successful garden space. Get a soil test to determine the macronutrients, micronutrients, and the soil pH. Your county’s Cooperative Extension office will send your soil sample to the state lab for analysis.

You may be tempted to skip this step, but any landscape architect worth his dirt will tell you that site and soil preparation is not the area in which to skimp. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are the macronutrients every plant must get from the soil. Soil tests should measure both phosphorus and potassium and make fertilizer recommendations. Nitrogen is not usually measured since it doesn’t last long in the soil, but the lab may make a standard recommendation.

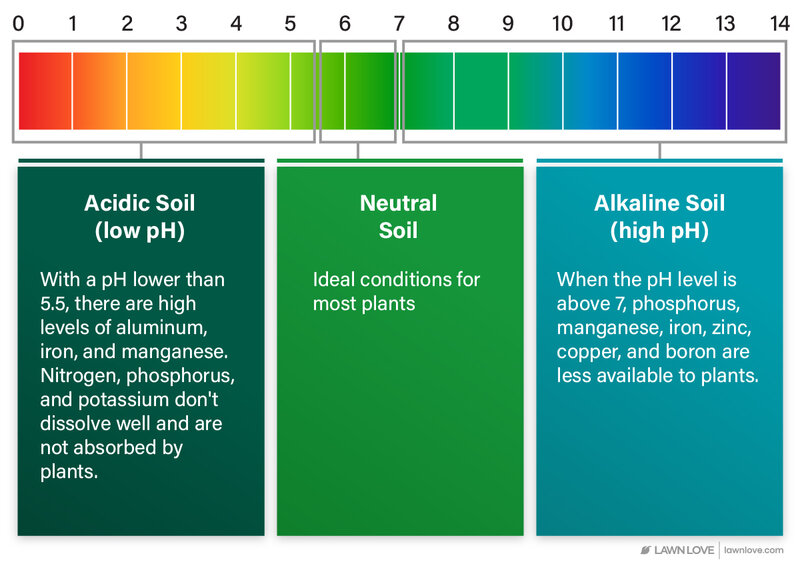

Some soil tests will measure secondary macronutrients and micronutrients as well. All of these nutrients must be in balance for each one to be properly absorbed by the plant. Soil pH — how acidic or alkaline the soil is — also affects nutrient absorption.

Before you install your new native species, follow the fertilizer recommendations for that growing area to ensure your plants have all they need to thrive.

Choose your plants

Now that you’re prepared for sun and soil conditions, it’s time to choose the right plants for this space. This is sometimes referred to as “right plant, right place.” Here are a few tips for success in your native garden.

Bypass marketing for a true native

Purchase straight species native plants or seeds. What is a straight species? All true native plants are straight species and have not been artificially bred to bring out certain traits. Cultivars of native plants, or “nativars,” have been altered by human breeding.

Here’s a simple boots-on-the-ground test to tell whether a native plant is a straight species or a cultivar: Look at its name. The first name you’ll see is its Latin name in italics (ex. Echinacea purpurea). Now see if it has a name after its Latin name. If so, and if it sounds like someone’s favorite smoothie flavor (such as Echinacea purpurea ‘Pink Double Delight’), it’s probably not a straight species. Someone brought it into a lab and bred it for a color, flower shape, or other desired trait.

Of course, you want to ensure that the plant is native to your local area, or at least to your state. A California native may not be a New England native, for example. A plant whose ancestors have lived with the other plants and animals in that area is a plant that is best suited for your climate and temperatures.

To get a little more technical, native plants are best sourced within your Level III ecoregion. (Ecoregions, short for ecological regions, are areas with similar ecosystems. Check out the Environmental Protection Agency’s Level III Ecoregion map to see the ecoregions in your state.)

To put it simply, plants and animals with a long ancestral history in your climate have grown up together, eaten the same foods, and endured the same weather. There’s no cultural adjustment; this is their home, and they know just how to survive and thrive in your landscape.

Climate and temperature aren’t the only aspects to consider. Pollinators and wildlife may not interact with a nativar in the same way as a straight species. Some nativars have altered flower shapes and sizes. This can make it impossible for a bee or hummingbird, for example, to gather nectar or pollen from these altered flower shapes. In addition, if these flowers are sterile, they do not produce seeds, and birds cannot feast on them as they could on a straight species native.

Aim for year-round interest

Don’t you want a beautiful garden year-round? Design it, and make it so. If this is too much for your schedule, you can always hire a landscape designer or landscape architect for professional guidance. If you’re starting small, this is a doable DIY project.

When shopping for plants, it’s tempting to choose a plant because it has beautiful blooms. When you look at a plant picture in a seed or online catalog, dig a little deeper before you click “buy.” Read the description to see when it blooms in your area. Try to choose perennials with overlapping bloom times. This is often called “four-season color.” If you plan it well, you may even have blooms in those dreary winter months.

Remember that native plants are more than a pretty face…er, flower. Native trees, shrubs, and grasses all play a part in local biodiversity. When you look at your state’s native plant list, don’t skip over these other elements and head straight for the wildflowers. Non-flowering elements — such as some native grasses — add depth, interest, and four-season provision for the wildlife in your native landscape. Design from the ground covers to the skies for the most effective and comprehensive native plant design.

Pro Tip: For large landscaping projects, install the tallest or largest elements first, and work your way down to the smallest. This prevents you from stepping on or rolling over smaller plantings as you install the largest features in the landscape.

Learn more about native plants in your city

Check out these local resources to learn more about your area’s native plants.

Check out your state’s native plant society

Most state native plant societies have well-developed websites with blog posts, native plant lists for your state, plant sale information, and contact information for the local chapters. They are your go-to resource for native plants.

In states with varying climates, there may be more than one plant list to consider. For example, local arboretums may have a list in addition to the one put out by the state native plant society. Choose the list that is closest to you for the best results.

Visit a local arboretum, wildlife sanctuary, or nature trail

These places often have plaques throughout that inform visitors about the plants, animals, and ecosystems they inhabit. These in-person visits are a great way to see plants “in action” and glean ideas for your native garden.

Birds, bees, and trees

State or local ornithological societies, beekeepers associations, and city tree groups are great places to get out, volunteer, and learn about plants and wildlife in your community.

What is a “tree group?” These are nonprofits that are most common in large cities (ex. “Tree San Diego). Their goal is usually to restore the tree canopy in a city and/or remove invasive species. They are always eager for volunteers to spend a day planting and taking care of local trees.

FAQ about how to design a native plant garden

A native plant is a plant that “occurs naturally in the place where it evolved.” In other words, its ancestors have lived there, too, for many, many generations, and it has not been altered by human breeding efforts. Check out our article, “What is a Native Plant” for more information.

Native plants benefit the local ecosystem, but they also benefit you as a homeowner and novice landscape designer:

—Few or no chemicals and pesticides

—Increase local wildlife habitat

—Reduce fertilizer use

—Low maintenance (saves time and money over the long haul)

—Less mowing

Local garden centers and nurseries are a good place to start. Independent stores may be more likely to offer native plants than big box hardware stores. Call a few in your area before you stop by and ask what they offer.

Also, ask where they source their plants. As we mentioned earlier, plants that have a lineage in your local area or climate are the best options for you, the success of the plants, and local wildlife.

Need more time on your weekend? Let our local lawn care pros take care of the mowing and keep your native garden fit for flyers and humans alike.

Main Photo Credit: Ron Frazier | Flickr | CC BY 2.0