In the middle belt of the country, extending from California to Virginia, choosing the right grass for your lawn can be a middling experience at best. In the North, cool-season grasses are the coolest choices for short summers and cold winters. In the South, warm-season grasses are the hottest grasses in town for mild winters and scorching summers. But trying to grow grass in the middle region of the U.S. can make you feel a little like Goldilocks.

Before you fling a random assortment of grass seeds across your lawn, let’s go through which grasses are “just right” for your Transition Zone lawn.

- What is the Transition Zone?

- What’s the problem with growing grass in the Transition Zone?

- Growth qualities of cool-season vs. warm-season grass

- How to choose grass based on your lawn

- Best grasses for your Transition Zone lawn

- Warm-season grass for the Transition Zone

- Cool-season grass for the Transition Zone

- FAQ about growing grass in the Transition Zone

- Taking care of your Transition Zone lawn

What is the Transition Zone?

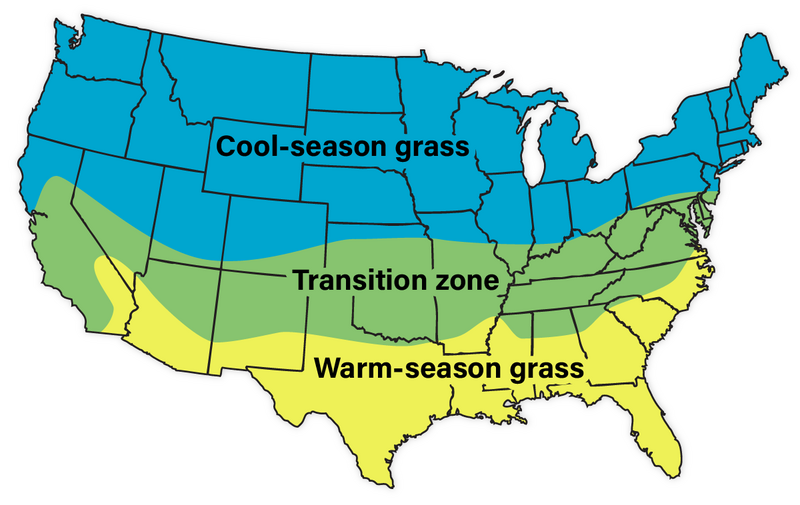

The Transition Zone is the belt of land sandwiched between warm and cool growing regions. It’s where lawns experience both scorching summers and freezing winters, making it tough to choose a grass that won’t burn in summer or freeze in winter.

The 5 growing regions

The U.S. has five distinct turf-growing regions where cool-season or warm-season grasses grow. Cool-season grasses grow in colder, northern climates and are well-adapted to freezing winters, while warm-season grasses do well in warmer, southern climates with hot summers.

Cool-season grasses thrive in the first three zones, and warm-season grasses love the last two.

1. The cool, humid Northeast and Midwest

2. The cool, humid Pacific Northwest

3. The cool, arid Great Plains and Intermountain West (between the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada)

4. The warm, humid Southeast and Gulf states

5. The warm, arid Southwest

The Transition Zone overlaps these distinct regions, except for the Pacific Northwest. It includes parts of California; Nevada; Arizona; New Mexico; southern Utah and Colorado; northern Texas; Oklahoma; Kansas; Missouri; Arkansas; northern Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia; Tennessee; Kentucky; South Carolina; North Carolina; West Virginia; Virginia; Maryland; Delaware; southern Pennsylvania; and New Jersey.

What’s the problem with growing grass in the Transition Zone?

Instead of getting the best of both worlds, the Transition Zone gets a pretty raw deal. Warm-season grasses that thrive in the South can’t stand up to the Transition Zone’s cold winters, and cool-season grasses that grow in the North can’t deal with the hot summers.

In other words, it’s hard to get a year-round green lawn in the Transition Zone. You end up with either a lovely green lawn in summer and a brown one in winter, or a healthy lawn in winter and a wilted yellow one in summer.

So how do you figure out which grass to grow in your Transition Zone lawn? Let’s start with the big question: Do you need cool-season grass that won’t faint on a warm day, warm-season grass that won’t freeze its blades off, or a mix of both?

Growth qualities of cool-season vs. warm-season grass

It’s tough to grow grass in the Transition Zone because there isn’t a turfgrass type specifically adapted to thrive in a climate with both hot and cold extremes.

Turfgrasses come in two varieties based on their preferred growing climate: Cool-season and warm-season. What makes them different? Biologically, it comes down to how they fix carbon dioxide to photosynthesize. Those photosynthetic differences mean they require different temperatures and environments to grow. Here are the growing qualities you can expect from each.

Cool-season grass

Cool-season grasses grow in the North, where winters are cold and summers are mild. Hot summers are the main hurdle for cool-season grasses: As temperatures warm up, they require more photosynthetic energy to stay green. When summers are too hot, cool-season grass goes dormant (turns brown).

Cool-season growing specifications:

- Growth begins when soil temperatures warm to 40-45 degrees Fahrenheit

- Ideal growing temperature: 65-75 degrees Fahrenheit

- Most vigorous growth periods: Early spring and fall

- Goes dormant in hot summers (over 90 degrees Fahrenheit)

- Grows less efficiently as temperatures rise: Requires more water in summer

- More cold-hardy than warm-season grasses

Common cool-season grasses:

- Annual ryegrass (Lolium multiflorum)

- Creeping bentgrass (Agrostis palustris)

- Creeping red fescue (Festuca rubra var. rubra)

- Hard fescue (Festuca ovina)

- Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis)

- Orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata L.)

- Perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne)

- Tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea)

Warm-season grass

Warm-season grasses thrive in the South, where summers are hot and winters are mild. Winters can be stressful for warm-season grasses and they go dormant when temperatures drop too low. They’re highly efficient photosynthesizers and require less water than cool-season grasses.

Warm-season growing specifications:

- Growth begins when soil temperatures warm to 60-65 degrees Fahrenheit

- Ideal growing temperature: 90-95 degrees Fahrenheit

- Most vigorous growth period: Summer (July to September)

- Goes dormant in cold winters (below 50 degrees Fahrenheit)

- More efficient at photosynthesis in hot weather

- Require less water than cool-season grasses

- More drought-tolerant than cool-season grasses

Common warm-season grasses:

- Bahiagrass (Paspalum notatum)

- Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon)

- Buffalograss (Buchloe dactyloides)

- Carpetgrass (Axonopus affinis)

- Centipedegrass (Eremochloa ophiuroides)

- St. Augustine (Stenotaphrum secundatum)

- Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum)

- Zoysiagrass (Zoysia japonica)

How to choose grass based on your lawn

If you live in the Transition Zone, your grass choice is less straightforward than that of a homeowner in, say, Maine or Florida. So how do you make sure your lawn gets a healthy, green start? Test your soil, evaluate your lawn’s sun exposure, and talk to your neighbors about what type of grass they use.

- Determine your soil type: Is your soil sandy, clay, silty, or loamy?

- Test soil pH: Is your soil more acidic, neutral, or alkaline?

- Calculate sun exposure: How many hours of sunlight does your lawn get each day?

- Consider foot traffic: Do kids and pets often play in your yard?

- Talk to your neighbors: What grass seeds do they use, and how much maintenance do they have to do to keep their lawn green?

- Contact your local cooperative extension office for advice on the best types of grass for your region.

As you read on about the pros and cons of cool- and warm-season grasses, consider how certain grasses can complement your lawn conditions.

For example, if your kids love running around your yard in the summer, a tough warm-season grass like bermudagrass or Zoysiagrass could be best. If your lawn is prone to shade, a mixture of fine fescue, Kentucky bluegrass, and tall fescue can keep your lawn healthy and prevent brown patches.

Weighing your options

When choosing a grass, ask yourself which is more important to you: A lush lawn in summer or green grass in winter.

If you love hosting summer lawn parties and want your neighbors to “ooh” and “aah” at your beautiful green lawn, warm-season grass is your best option. It may not be as gorgeous in the winter, but you’ll have plenty of summer fun.

If you’re out of town during the summer and your lawn is the last thing on your mind, go with cool-season grass (you’ll still need someone to water it while you’re away). That way, you’ll have gorgeous greenery in winter.

Keep your expectations realistic: When temperatures fluctuate to one extreme or the other, your grass may go dormant, and with proper dormancy care, your grass will grow back green and healthy.

Pro Tip: You may need to amend your soil to give your grass the soil texture, nutrients, and pH level that it needs.

Best grasses for your Transition Zone lawn

Homeowners in the Transition Zone used to choose cool-season grasses over warm-season ones to avoid winter dormancy. However, as global temperatures rise and warm-season grasses improve in hardiness, homeowners are switching to warm-season grasses.

Many are now choosing Zoysiagrass and bermudagrass (both warm-season grasses). Homeowners with bermudagrass often overseed with annual or perennial ryegrass for a green lawn year-round.

Warm-season grass for the Transition Zone

If you live in the southern portion of the Transition Zone, two types of grass will stand up to the heat and the cold: Zoysia and bermuda. They’ll stay evergreen in most areas of the “northern South.”

Benefits of warm-season grass

- Requires less watering and maintenance than cool-season grass

- Fewer pest problems

- More disease-resistant

- Highly drought- and heat-tolerant

- More environmentally friendly

- Stands up to heavy summer foot traffic

- New varieties are cold-hardy

Disadvantages of warm-season grass

- Takes longer to green up in the spring

- More expensive to establish: Usually grown from sod

- Loses its color in winter

- May die if exposed to prolonged freezing weather

- Patchy areas require reseeding after the first winter

- Prone to thatch

How to maintain warm-season grass

- Overseed with a cool-season grass in early fall for green color in winter

- Dethatch when the thatch layer is over half an inch thick

- Aerate yearly in late spring to early summer

Bermudagrass

Bermudagrass, also known as wiregrass or devilgrass, is one of the most popular grasses in the South and Transition Zone: It’s a speedy grower that thrives in most soil types and handles heavy foot traffic like a champ.

Bermuda spreads via both stolons (above ground stems) and rhizomes (underground runners), making a dense, robust plant that won’t damage easily. It’s easier to mow than Zoysia, and it’ll bounce back if you accidentally mow too low. Plus, it’s cheaper and more drought-tolerant than Zoysia.

The downside? Bermuda requires a whole lot of sun. If your lawn is partially shaded, go with Zoysia.

Best varieties for the Transition Zone: Old bermudagrass varieties struggled with cold weather, but several new cultivars tolerate low temperatures. Yukon, Latitude 36, and Riviera are the most cold-hardy cultivars of bermudagrass.

Zoysiagrass

Zoysia is a coarse, light-green grass that is more cold-hardy and shade-tolerant than bermudagrass, and it can grow farther north. It’s highly drought-and heat-tolerant, grows well in most soil types, and resists pests once established.

Zoysia takes a while to establish and grows much more slowly than bermuda, but once it has filled your lawn, it requires very little maintenance. Zoysia does not need frequent mowing, and its density acts as a built-in weed prevention system.

Best varieties for the Transition Zone:

In cooler, northern areas of the transition zone, choose Belaire, Empire, Palisades, or Meyer cultivars.

In warmer, southern regions, choose Innovation, Zorro (excellent shade tolerance), El Toro, Empire, Palisades, Meyer, or Zeon cultivars.

Cool-season grass for the Transition Zone

The best cool-season grasses for the Transition Zone are tall fescues, fine fescues, Kentucky bluegrass, and perennial ryegrass. If you go to a garden store, you’ll find them sold as mixes.

Benefits of cool-season grass

- Less expensive to establish than warm-season grasses

- Generally more shade-tolerant

- High cold tolerance

- Won’t thin out in winter

Disadvantages of cool-season grass

- Loses color in summer

- More fertilizer and pesticide needed

- More prone to diseases like brown patch

How to maintain cool-season grass

- Apply fertilizer in spring, and then on a 6-8 week schedule through the growing season

- Avoid low mowing in summer

- Increase watering in hot summer months

- Apply pesticide when needed

Tall fescue

Tall “turf-type” fescue is a hardy, low-maintenance all-star. It boasts the deepest root system of the cool-season grasses, making it especially drought-resistant. With fine leaves and a dense growing habit, tall fescue grass grows well in full sun to partial shade, has a high heat tolerance, and does well in moist clay soils. It’s also highly pest-resistant and withstands heavy foot traffic.

The downside? Tall fescue can grow a bit too well. During peak growth, it requires mowing about every six days.

Tall fescue is slow to recover from damage, so it’s often mixed with Kentucky bluegrass or perennial ryegrass to ensure lawn uniformity.

Kentucky bluegrass

With emerald blades that are soft to the touch, Kentucky bluegrass is a favorite of homeowners across the country. It’s gorgeous, exceptionally cold-hardy, and soft on your feet (and your puppy’s paws). Kentucky bluegrass has a slow germination rate (14-21 days) and takes months to establish, but once it’s established, it spreads quickly via rhizomes.

Kentucky bluegrass requires more maintenance than the other cool-season grasses, and it’s less drought- and heat-tolerant than tall fescue. It needs more water and fertilizer during the summer months, and without routine mowing and fertilizing, it’s prone to disease and thatch buildup.

It’s often seeded with tall fescue or perennial ryegrass to prevent pests and ensure lawn uniformity, or with fine fescues to cover lawns that have both sun and shade.

Fine fescue

If you want a low-mow lawn, fine fescues (like creeping red, hard, or chewings fescue) will save the day. Fine fescues have the highest shade tolerance of all the cool-season grasses, and they’re perfect for lawns with poor, dry soil. They are drought-tolerant, naturally crowd out weeds, and won’t require fertilizer or herbicide.

The downsides? Fine fescues can’t stand up to heat like tall fescue can, and they aren’t a great choice if kids and pets often play in your yard: They can only handle moderate foot traffic. Likewise, you’ll want to choose another cool-season grass (like tall fescue) if you have heavy clay soil.

Fine fescues are often mixed with the other cool-season grasses. They pair well with Kentucky bluegrass in sun-and-shade seed blends.

Perennial ryegrass

Perennial ryegrass is a glossy-leaved, speedy lawn hero that germinates in just 7-10 days and grows densely, making it a fantastic choice for heavily trafficked lawns. It thrives in full sun but can grow in partial shade, and it naturally resists disease and insects.

It’s not as heat- or drought-tolerant as other cool-season grasses, so it grows best in the northern part of the Transition Zone and is often mixed with another grass like Kentucky bluegrass (80-90 percent perennial ryegrass, 10-20 percent Kentucky bluegrass).

Perennial ryegrass is perfect for overseeding southern bermudagrass lawns in the fall to keep them green in the winter.

Pro Tip: Seed mixtures should contain no more than 20 percent perennial ryegrass. Otherwise, the ryegrass will crowd out other grasses.

FAQ about growing grass in the Transition Zone

1. What is dormancy?

Don’t rush to recite a eulogy when your grass turns brown during the summer heat or winter freeze. It probably isn’t dead. Rather, it’s dormant.

Dormancy is a survival tactic for grass under stress. In freezing or scorching weather, grass completely stops growing to preserve its energy and nutrients. Basically, dormancy is a long winter’s (or summer’s) nap for your grass.

In the Transition Zone, grasses are more prone to dormancy because they’re under more stress, either in summer or winter. You can combat dormancy by choosing hardy grasses and overseeding with compatible seeds.

When grasses are dormant, let them sleep. Don’t wake them up by applying fertilizer; they’ll wake up on their own when it’s safe to grow again.

2. Will high-nitrogen fertilizer help my cool-season grasses grow in summer?

Not in the long run. It’s a common misconception that high-nitrogen fertilizer will keep cool-season grasses growing during hot summers. In reality, giving your grass too much nitrogen will force it to grow when it doesn’t have the energy to do so, which weakens the plant and leads to disease. It’s better to use an organic fertilizer during the summer months.

3. Do I need to water dormant grass?

Yes, it’s important to give your dormant grass water to prevent plant death. In summer, water dormant grass ½ inch every two weeks.

In winter, give your dormant grass ½ to 1 inch of water every week as long as the air temperature is 40 degrees Fahrenheit or above. Never water when temperatures are below 40 degrees Fahrenheit or when snow, ice, or frost is present, as this can result in frozen grass and plant death.

4. When do I plant cool-season or warm-season grasses?

Plant cool-season grasses in early fall, at least 45 days before the first frost. Seed warm-season grasses in late spring to early summer.

5. What is the recommended mowing height for my grass?

| Grass type | Ideal height for lawns | Mow grass at this height |

| Fine fescues | 2.5 – 3 inches | 3.25 – 4 inches |

| Kentucky bluegrass | 2.5 – 3.5 inches | 3.25 – 4.5 inches |

| Perennial ryegrass | 1.5 – 2.5 inches | 2 – 3.25 inches |

| Tall fescue | 3 – 4 inches | 4 – 5.25 inches |

| Bermuda | 1 – 2 inches | 1.25 – 2.5 inches |

| Zoysia | 1 – 2 inches | 1.25 – 2.5 inches |

6. How often should I mow my grass?

Mowing once a week is generally the best practice. Use the one-third rule to determine whether your grass needs mowing: Mow when your grass reaches one-third higher than the recommended mowing height. Never remove more than one-third of the total height of your grass.

Taking care of your Transition Zone lawn

It takes some discovery to find the grass that’s “just right” for your Transition Zone lawn. Choosing a hardy grass or mix will help you minimize lawn stress and keep your grass green for most of the year.

Want a hand with the yard chores? Contact a local lawn care pro to keep your new lawn healthy and happy, so you can stop playing Goldilocks with your grass.

Main Photo Credit: musthaqsms | Pixabay