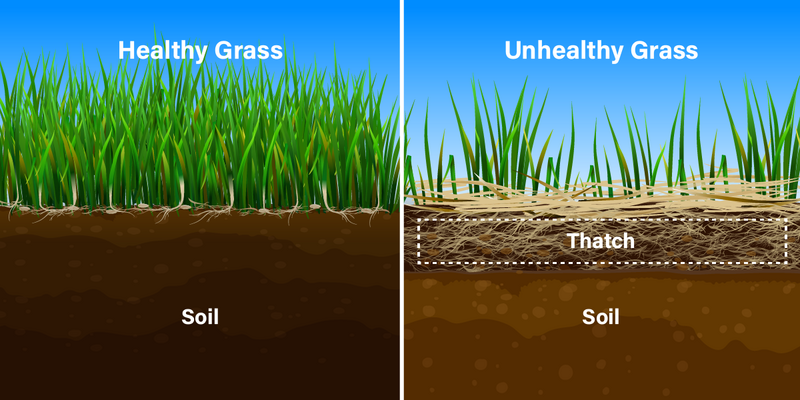

Many homeowners wonder, “What is thatch?” It’s a common topic in lawn care, and understanding its significance is crucial for maintaining the health and beauty of your lawn.

If walking on your lawn gives you a spongy, squishy, or sinking feeling, you might have thatch. A small amount of thatch helps your lawn, but too much means stunted roots and the potential for fungus and pest problems. Learn more about thatch, its pros and cons, why it accumulates in your lawn, and how to effectively manage it.

What is thatch?

Thatch is a layer of undigested roots, leaves, and organic plant material that settles between the turfgrass and the soil surface. It forms as a result of the natural process of grass growth and decay. In a balanced lawn ecosystem, microorganisms like fungi and bacteria help break down this organic matter, recycling it back into the soil as valuable nutrients.

However, when the rate of organic matter production exceeds the rate of decomposition, thatch starts to accumulate. If you take a core sample of a thatchy lawn, the thatch layer squishes down and rebounds like a wet sponge.

The thatch layer not only looks spongy but also functions as a sponge. Most of the water from rain or irrigation is trapped in this layer of organic matter. And because the water remains at the thatch layer, the grassroots won’t have any reason to grow deep in search of water.

What causes thatch buildup?

Understanding what causes thatch buildup is crucial for effective management. Contributing factors include an overabundance of grass clippings, dead leaves, and other organic debris that don’t break down quickly enough.

Several factors can lead to excessive thatch accumulation, including:

- Overfertilization: Excessive use of nitrogen fertilizers can stimulate rapid grass growth, leading to more thatch production than decomposition. Plus, using pesticides and fungicides regularly may encourage excessive lawn thatch.

- Inadequate aeration: Compacted soil and poor aeration can reduce the activity of microorganisms responsible for breaking down thatch.

- Improper mowing: Infrequent or improper mowing practices can contribute to thatch buildup.

- High soil pH: Soil with a high pH (alkaline soil) can slow down the decomposition process, allowing thatch to accumulate.

- Lack of microorganisms: Soils with insufficient populations of beneficial microorganisms may struggle to break down organic matter effectively.

Pro tip: To determine if you have a thatch problem, take a core or plug of soil from several areas in your lawn. If there is a layer of spongy, undigested material between the grass and soil, this is the layer of thatch.

Pros and cons of thatch

If a large amount of thatch develops on your lawn, it can do more harm than good. Up to one-half inch thick of thatch is fine, but anything over that, and you’ll need to remove some of the material.

Pros of thatch

A thin layer of thatch (less than one-half inch) provides these benefits to your lawn:

- Insulates the soil

- Maintains soil moisture

- Reduces weed germination

- Protects from heavy foot traffic

- Creates a resilient, soft walking surface

- Protects grassroots from extreme heat and cold

- Prevents soil erosion caused by heavy rainfall or irrigation

Cons of thatch

A thick layer of thatch (more than one-half inch) can be a detriment to your lawn:

- Results in shallow root systems

- Roots may dry out in hot weather

- Provides an ideal habitat for fungus and pests

- Causes soil compaction issues that hinder root growth

- During the rainy season, roots are too wet and deprived of oxygen

- Blocks air, water, fertilizers, and lawn treatments from reaching the root zone

Note: With too much thatch, it would be easier for lawn mowers to scalp the lawn since the wheels sink into the soil and the crowns are higher than normal.

Which grasses develop thatch?

Certain grass types are more prone to thatch than others. Most grasses that develop stolons (above-ground stems) or rhizomes (below-ground stems) are susceptible to excessive thatch buildup. Grasses with greater lignin content are more prone as well because lignin is harder for microorganisms to break down.

The cool-season grass types most susceptible to thatch include:

- Creeping bentgrass

- Creeping red fescue

- Kentucky bluegrass

For warm-season grasses, the following are susceptible to thatch:

- Hybrid bermudagrass

- Centipedegrass (only if over-fertilized)

- St. Augustinegrass

- Zoysiagrass

Note: Since perennial ryegrass and tall fescue are bunch-forming grass types, they are not as susceptible to thatch. But like other grass varieties, they still need proper maintenance, as other factors (mentioned above) can still cause thatch buildup.

Signs your lawn needs dethatching

Knowing when your lawn needs dethatching is essential for maintaining its health and appearance. Keep an eye out for the following indicators:

- Your lawn feels spongy: A soft and spongy lawn indicates there is excessive thatch between the soil and grass.

- Increased water runoff: Water fails to penetrate the soil and instead runs off the surface, leading to poor absorption.

- Poor grass growth: Despite proper care, your grass shows stunted growth, thinning, or yellowing.

- Lackluster appearance: Your lawn looks dull, lacks vibrancy, and has a generally unhealthy appearance.

Benefits of dethatching your lawn

Dethatching can do wonders for your lawn’s health. It offers numerous advantages, including:

- Improves nutrient and water absorption: Removing excess thatch allows essential nutrients, water, and air to penetrate the soil more effectively. This results in improved nutrient uptake by grassroots, promoting healthier and more vigorous growth.

- Enhances grass density: Thatch removal creates space for new grass shoots to emerge and fill in bare patches. This leads to a denser and more lush lawn better equipped to resist weeds.

- Helps prevent disease: Thatch is a breeding ground for harmful pests and disease pathogens. Dethatching reduces these habitats, lowering the risk of disease outbreaks and pest infestations.

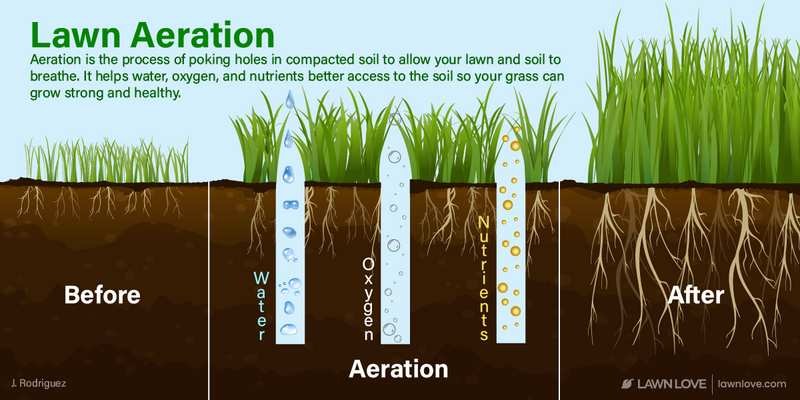

- Improves aeration: Dethatching enhances soil aeration of compacted soil caused by thick thatch layers. Well-aerated soil encourages deeper root growth and better overall grass health.

- Enhances curb appeal: A dethatched lawn looks tidier and more attractive, with a uniform and vibrant green appearance that can significantly boost your home’s curb appeal.

These benefits, in turn, result in a greener, more resilient lawn better equipped to withstand environmental stressors.

How to get rid of excess thatch in your lawn

There are several methods for removing excess thatch from your lawn. Choose the best one that suits your lawn’s needs and your available resources:

- Manual dethatching: Using a dethatching rake or dethatching machine, physically remove the thatch by vigorously raking the lawn. This method is suitable for smaller lawns.

- Mechanical dethatching: For larger lawns, consider using a power rake, dethatcher, or scarifier, which efficiently removes thatch by cutting into the soil and loosening the layer.

- Vertical mowing: This method involves using a vertical mower, also known as a verticutter, to cut through the thatch and soil surface, lifting and removing the debris.

- Core aeration: While primarily used to alleviate soil compaction, core aeration also helps reduce thatch buildup. After doing core aeration, apply a layer of topdressing to your lawn.

When to dethatch your lawn

The optimal time for dethatching depends on the type of grass in your lawn and your local climate. As a general guideline:

- For cool-season grasses like Kentucky bluegrass and fescue, the best times for dethatching are early fall or late summer. This allows your lawn to recover and grow vigorously during the cooler months.

- For warm-season grasses like bermudagrass and Zoysiagrass, it’s best to dethatch them in late spring or early summer. This is the time when they are actively growing and can recover quickly.

- If you have a mixture of grass types or live in a region with a moderate climate, consider dethatching during the transitional seasons of spring and fall when temperatures are milder.

What to do after dethatching your lawn

After dethatching, your lawn will require some post-treatment care to ensure a full recovery. Perform these essential steps to help your grass thrive:

- Remove debris: Collect and remove the debris and thatch material from the lawn to prevent it from interfering with grass growth.

- Overseed: Consider overseeding the lawn, as filling bare spots with the appropriate grass seed can help promote even growth.

- Fertilize: Apply a balanced fertilizer to provide essential nutrients to the grass, encouraging strong and healthy regrowth.

- Water: Keep the lawn adequately watered during the recovery period, ensuring the soil remains consistently moist but not waterlogged.

- Adjust mowing height: Raise the mower height temporarily to reduce stress on the grass as it recovers.

How to prevent thatch buildup

Even if you have thatch-prone grass, there are ways to encourage a healthy climate of microorganisms that break down thatch quickly.

1. Continue to mulch your grass clippings

In most cases, grass clippings will not contribute to an excessive layer of thatch. Leaving mulched grass clippings on the lawn can be beneficial and is a key lawn care practice for a healthy lawn.

2. Follow the “deep and infrequent” rule of watering

Don’t water your lawn every day, or even every other day. (Sandy soils may be an exception.) Aim for about 1 inch of water once per week (also take into account rainy weather). This encourages the grassroots to grow deep in their search for water.

Don’t know if it’s time to water? Let the grass be your guide. Look for wilting or curling leaf blades before you turn on the faucet.

3. Invite more microorganisms into your lawn

A soil pH of 6.5, along with aerated soil, is an ideal climate for microorganisms that break down thatch. Conversely, compacted, acidic soils with a soil pH of 5.5 or lower reduce the population of beneficial microbes in your lawn.

4. Go easy on the fertilizer

Highly managed lawns with too much nitrogen fertilizer encourage too much growth. Excessive root and stem tissue can’t be broken down that fast. In addition, some nitrogen fertilizers lower the pH of your soil and decrease the microorganisms in your lawn.

5. Watch out for fungicides and insecticides

Thatch problems often develop in high-maintenance lawns. Over several years, regular fungicide treatments can promote excessive root and rhizome growth, which leads to more thatch.

Certain insecticides decrease the earthworm population in your soil. Since earthworms help stimulate soil microbial activity, fewer earthworms mean less thatch is decomposed in your lawn.

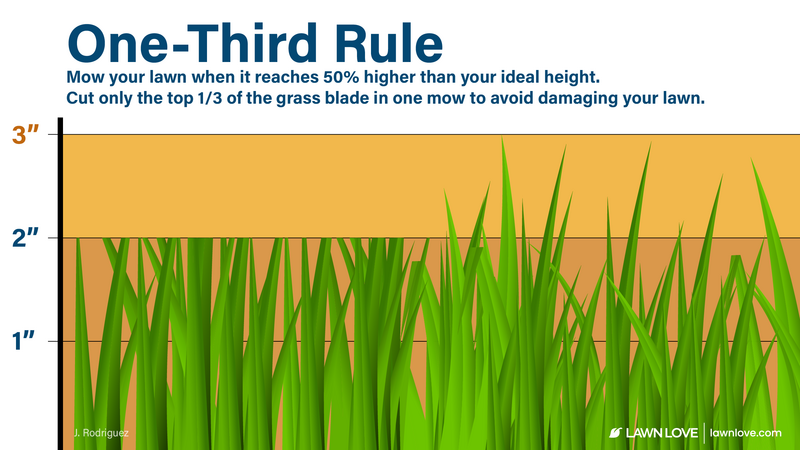

6. Follow the one-third rule of mowing

If you cut no more than one-third of the grass blade per mow, you reduce thatch production in your lawn. How? The tips of the grass are usually only leaf tissue, which is mostly water. If you cut more than that, you may cut more of the stem, which breaks down more slowly than the leaf.

FAQ about thatch

What’s the difference between dethatching and aeration?

Aeration helps alleviate compacted soil by poking holes in the soil while dethatching rakes up the thatch layer to prevent excessive thatch from causing serious problems for your lawn.

How can I measure thatch thickness?

To determine the thickness of your thatch:

- Use a shovel to remove a small, 3-inch-deep sample of your lawn.

- Measure the brown layer between the grass blades and the soil surface.

- If the brown layer is over half an inch long, your lawn could use dethatching.

Should I dethatch or aerate first?

If your lawn has both thatch and soil compaction problems, you may want to dethatch before aerating it.

Get rid of your thatch problem

Thatch may seem like a mysterious enemy lurking beneath your beautiful green lawn. But with an understanding of what thatch is, you can take proactive steps to keep it in check and maintain a lawn that’s the envy of the neighborhood.Contact a local lawn care pro today if you’d like the experts to take care of your thatch, compaction, and other lawn problems.

Main Photo Credit: David Eickhoff | Flickr | CC BY 2.0